The Work That Comes Before “Following the Money”

Product decision-making in the earliest stage

One of the hardest moments in early product work is realizing all the advice you’ve been given assumes something you don’t have yet: data, customers, or revenue.

When people tell you to “follow the money” or “build a business case,” they’re usually speaking from a place where money has already shown up. At pre-seed, pre-revenue, none of that exists yet. There are no deals to analyze, no funnels to optimize, no historical signals to lean on. Everything feels hypothetical because, in many ways, it is.

That doesn’t mean you’re stuck. It means your job is different from what advice assumes.

At this stage, you somehow have too many business opportunities and not enough real ones at the same time. Everything feels possible, but nothing feels concrete. Waiting for clarity isn’t an option. You need to act.

The problem is that the classic “follow the money” advice doesn’t make sense before your product is even formed.

This article covers a way of working that helps you move through ambiguity until a product direction starts to take shape.

Why having a way of working matters

Working through ambiguity is hard for most product managers. In early startups, the product manager role is often part-time or one of the first hires outside the founding team. There are endless possibilities and real constraints at the same time.

You bounce from engineering discussions to customer conversations to trying to define a target customer. It’s exhilarating. You’re making progress every day, yet there’s a persistent feeling that you’re missing something important.

Can you afford to pause and come up with a master plan? No. But you can rely on a way of working that keeps you moving while helping you learn your way forward.

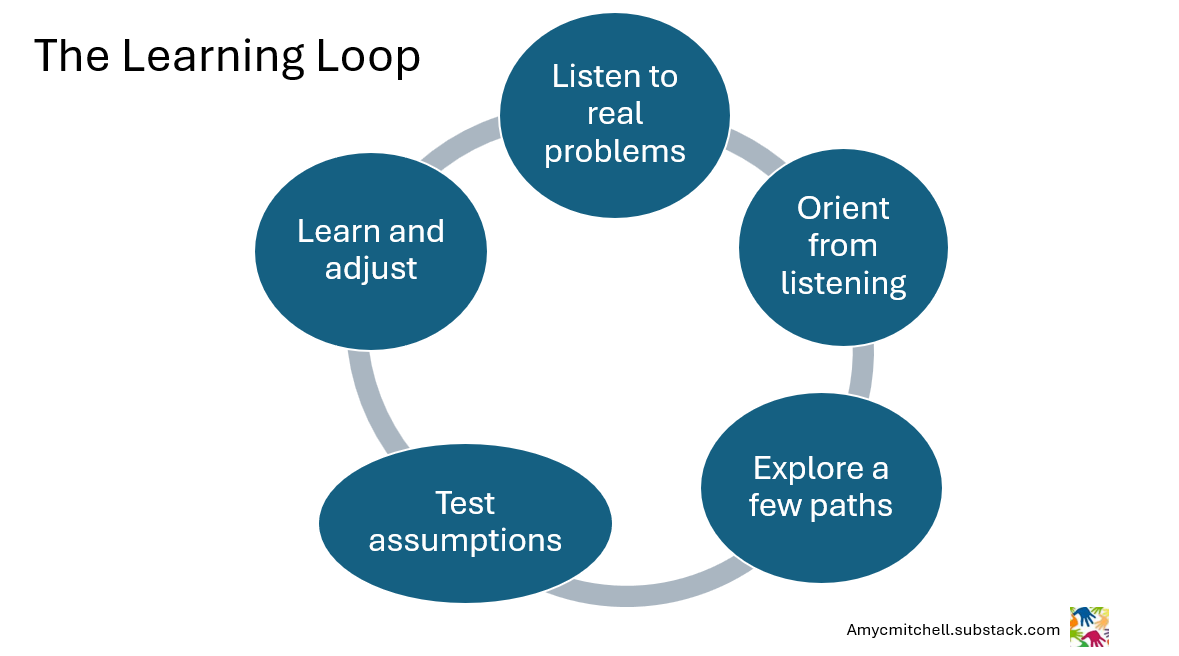

What follows isn’t a sequence to follow once. It’s a loop you move through, over and over, as you learn.

For paid subscribers: Walk through this learning loop with an example early-stage startup—showing how interviews, AI context, follow-up conversations, experiments, and early builds informed one another over time. It shows how direction emerges when you keep learning in motion.

Start where reality is: other people’s problems

You already have access to something valuable: people who are living with the problem related to your startup. And most of them are more than willing to talk about the workarounds they use today.

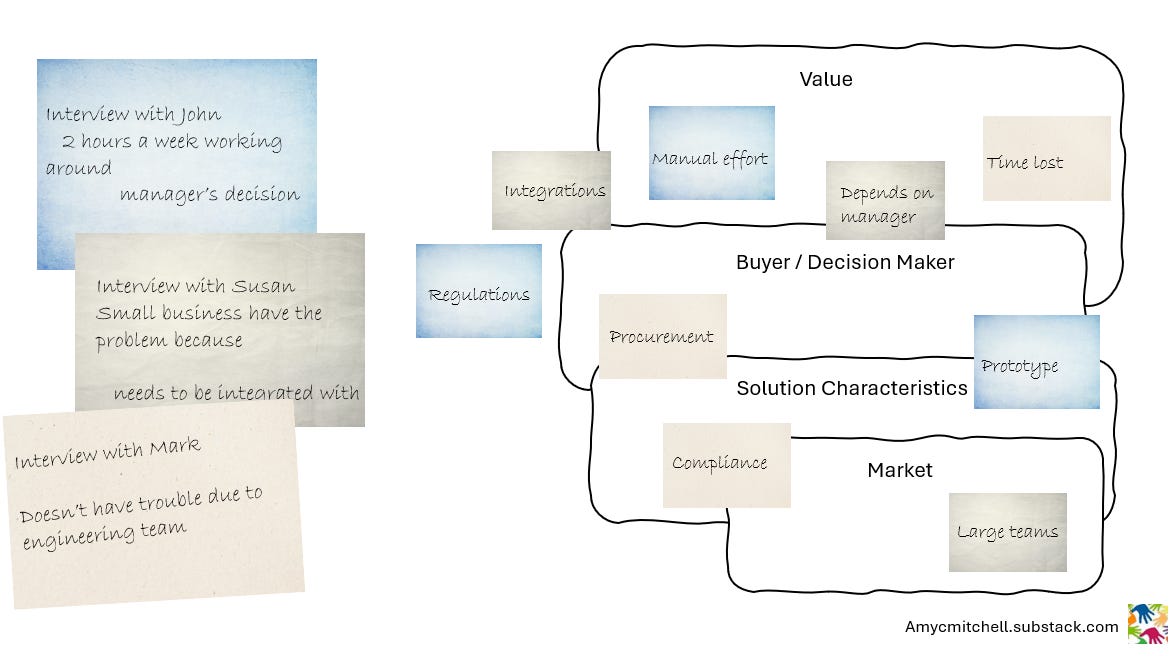

Your problem space is the door-opener. These conversations aren’t about pitching your product. They’re about learning the business impact of the problem. You’re trying to understand things like:

How much effort goes into working around the problem?

What does a “real” solution look like in their mind?

How do they decide to change the way they handle this today?

Who else has this problem, and what do they have in common?

It’s tempting to ask what they would buy. Don’t. This question shuts down learning before it starts. At this stage, you’re not selling; you’re learning how your future product would actually fit into their world.

If you listen carefully, these conversations tell you more than they first appear to:

The effort spent on workarounds hints at your upper bound on pricing. If the problem costs an hour a week, revenue per customer likely won’t exceed that value.

Their picture of a solution tells you how much product effort it will take to win. If they describe a “luxury” experience but you’re planning a prototype, this may not be the right early customer.

Their decision process tells you who actually buys. If no one seems to decide, your next interview needs to find the decision-maker.

Shared characteristics across interviews start to outline the size and shape of your market.

Take notes. Compare interviews. Connect the dots. Over time, a picture starts to form around problem size, viable product scope, and potential revenue.

As you hear similar things again and again, you’ll notice gaps in your understanding. That’s often the right moment to zoom out.

Use AI as a map, not an answer

Once you understand the problem from real people, AI becomes useful. But not before talking to potential customers.

If you go to AI too early, the best you’ll get is confirmation that the problem exists. Your specific product idea is almost always too new or too nuanced to show up meaningfully.

After several interviews, AI helps in a different way: it gives you orientation. You can explore adjacent markets, existing approaches, regulatory constraints, and historical attempts to solve similar problems.

This is more about orientation than validation. AI helps you see whether what you’re hearing is isolated or part of a broader pattern. AI sharpens the questions you ask next.

As your understanding deepens, possibilities start to emerge.

Narrow your thinking into a few paths

At some point, continuous learning becomes a trap. As patterns emerge, it helps to stop expanding and focus on a few paths.

Form two or three explicit hypotheses. Think of these as working theories that help you learn what to do next.

Each hypothesis should imply a different customer, a different monetization path, or a different reason someone would eventually pay. Don’t over-prioritize yet. It’s too early for that. What matters is that each path is plausible enough to test.

This is where you’ll discover some small experiments to learn more.

Experiment to learn, not to prove

As some paths become clearer, experimenting becomes the fastest way to keep learning.

Each hypothesis carries assumptions about customers, buying behavior, and product scope. But most of this you don’t know yet. Set up your experiments to surface which of those assumptions break first.

You don’t need many experiments. You need a few that bring out the right questions. Let each hypothesis guide you to the assumption that matters most. For example:

If the assumption is about customer type, talk directly to those people and see if the problem shows up.

If it’s about willingness to change, dig into their current process and what would need to shift.

If it’s about buying from you, show a mockup or prototype and probe for deal-breakers like procurement, security, or compliance.

These aren’t feel-good activities. They’re about eliminating paths that don’t make business sense.

Each experiment should sharpen your understanding of both the opportunity and the cost of pursuing it.

Build just enough and then go back to the beginning

Eventually, one hypothesis will feel less fragile than the others. That’s your signal to build. But focus on a learning goal as you build.

You put something in front of people. You watch how they react. Then you go right back to talking to customers. Their responses will change what you thought you knew, and the loop continues.

Over time, something shifts. The business direction stops feeling hypothetical. It starts to feel real. This way of working keeps pulling you toward what fits.

Conclusion: following the money before the money arrives

Direction comes from staying in motion long enough for the right answer to reveal itself. By the time revenue appears, you’ve learned your way into the business. You already understand the problem, the buyer, the tradeoffs, and the constraints.

That’s what this stage of product work is really about.

You’re not failing to “follow the money.” You’re doing the work that makes following it possible. You’re learning how value forms and which paths are worth committing to.

Direction emerges because you kept moving with intention. This turns ambiguity into progress as you go.

Related links:

Looking for more practical tips to develop your product management skills?

Free Product Manager Resources from Product Management IRL

Premium Product Manager Resources (paid only) 4 learning paths, 6 product management templates and 7 quick starts. New items monthly!

Connect with Amy on LinkedIn, Threads, Instagram, and Bluesky for product management insights daily.

Love this, shows clearly how to think of discovery and weaves in AI in a very healthy way