Alignment Isn’t the Problem

Product decisions stall when risk stays unspoken

Most product managers aren’t bad at alignment.

They’re bad at being handed an alignment problem that isn’t actually solvable at their level.

Conversations about requirements are full of opinions, tension, and stalled decisions. The common advice is “just get alignment.” But often, the real issue is that the organization hasn’t agreed on which risks are worth taking.

Until that tradeoff is explicit, alignment efforts circle the problem instead of resolving it.

The alignment trap product managers fall into

Product managers rely on alignment to deliver the right thing. When it works, alignment reduces rework, conflicting interpretations, and late surprises. In that sense, alignment is a form of risk management through leadership.

But product managers can’t override conflicting executive priorities. Even the strongest PMs struggle when misalignment exists upstream, beyond their ability to influence.

Why alignment breaks before requirements

Some issues are local and solvable within a team. Others are systemic and upstream from product. Before requirements are defined, it’s easy to blur the two.

Requirements debates are often proxy arguments. Stakeholders use requirements to protect their domain, such as engineering, sales, support, and marketing. But these same stakeholders won’t name the underlying risk they’re trying to avoid.

Product managers get pulled into translating concerns instead of helping the organization choose between tradeoffs.

The missing conversation: which risk can be accepted?

When the issue is upstream or systemic, alignment doesn’t come from rallying around a goal. Alignment happens faster when risk is made explicit.

But risk is subjective. People disagree on timing, impact, and who bears the cost. Multiple risks, multiple opinions. And the organization avoids choosing.

When teams ask for “flexibility,” they often haven’t agreed on where judgment should live.

A practical way to unblock alignment

When alignment stalls, the job is to surface the risk tradeoff the team is avoiding and make it discussable. In practice, that means shifting the conversation in three ways.

First, stop debating proposals and ask what failure each stakeholder is trying to prevent. Most disagreements make sense once you name the risk behind them.

Second, ask which failure would be worse. Which downside the organization is more willing to live with.

Third, clarify where judgment should live by default. Should most cases flow automatically, or should humans intervene unless conditions are clearly safe?

Alignment improves when teams agree on a default path. This is because defaults decide where risk is absorbed without debate.

A default doesn’t eliminate exceptions. It makes exceptions intentional.

The question of default path vs judgment path shows up across products in different forms. One common version is deciding what should happen by default vs when it’s worth slowing down for human judgment.

A concrete example: Automation vs manual handling

Consider a software upgrade flow. Customers expect upgrades to happen automatically. But when upgrades fail, recovery often requires manual intervention by the user or the supplier.

Deciding how much to automate failure handling exposes competing risk concerns.

The stakeholder opinions about further automation for upgrade failures are:

Engineering feels it is safest for users to manually handle upgrade failures

Marketing says customers will raise issues if any upgrade appears to fail

Support prefers full automation to reduce irate customer situations

Sales wants customers to delay upgrades so there aren’t any issues preventing new sales

Each position is reasonable on its own. The problem is that the underlying risk tradeoffs haven’t been made explicit.

Risk gradients

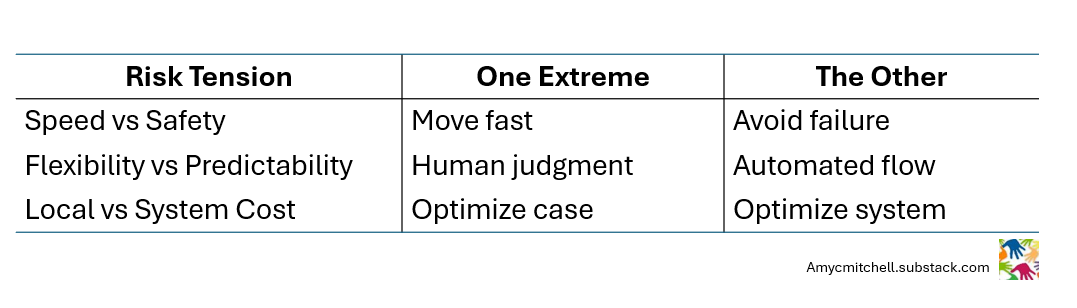

A way to consider failure impacts is with a risk gradient. Depending on your customers, business objectives and product maturity, the risks fall on a gradient. The risk gradients are:

Speed vs safety

Flexibility vs predictability

Local change vs system costs

Consider for each risk gradient what people want to avoid. This is what’s holding up your product decisions and requirements.

Surface the risk that is holding alignment

Anchor one concrete example to surface that risk. For the upgrade situation with failures, you hear the following:

Risk 1: Speed vs safety:

Upgrades are faster if the failures are handled automatically

Upgrade issue handling is safer with manual intervention

Risk 2: Flexibility vs predictability

Manual handling is more flexible with expert judgment

Upgrades need to have a predictable conclusion

Risk 3: Local optimization vs system cost

The user knows the criticality of the upgrade for best manual treatment

The system loses trust every time an upgrade needs manual help

You prepare a concrete example to represent the risks:

Your lead customer upgrades and has to take manual action to finish

Your newest customer upgrades and it just works

Then ask:

Do we want customers to spend time recovering from an upgrade?

At what point in an upgrade failure do we want to get involved?

When teams are ready to discuss acceptable upgrade failures, then you can create a summary for validation with leaders.

Your role as the product manager

When the alignment is stalled due to structural issues outside of your control, your job isn’t alignment. Your role is to make the cost of indecision apparent.

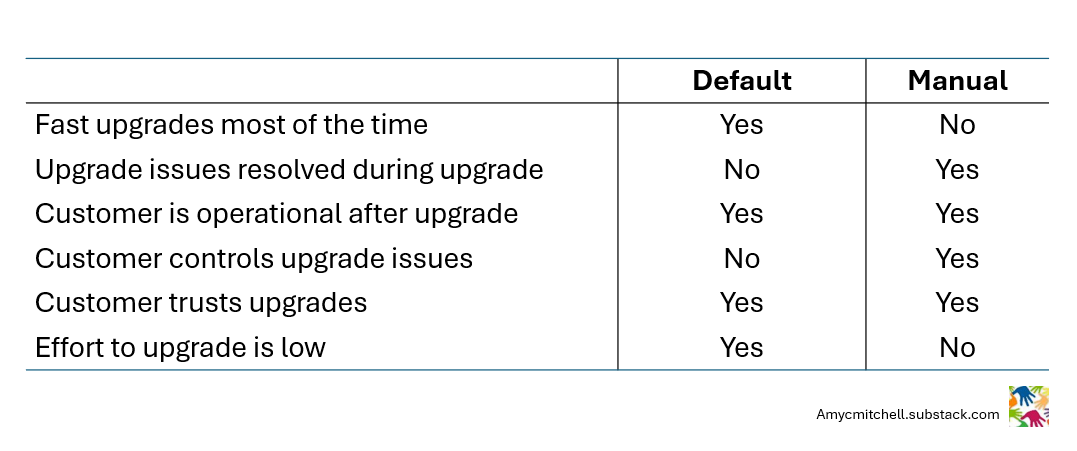

On the upgrade and failure decision, you can show the tradeoffs of manual intervention:

No option checks every box.

This isn’t about winning an argument. It’s about helping the organization choose deliberately instead of drifting into complexity.

Closing - redefining “being good at alignment.”

Being good at alignment doesn’t mean making everyone agree.

It means helping the organization see the tradeoffs it’s already making. And choose tradeoffs deliberately instead of by default.

When alignment stalls due to structural issues outside your control, your role isn’t to force consensus. It’s to make the cost of indecision visible.

Make risk visible.

Choose the worse failure.

Define the default.

Sometimes, the most strategic thing a product manager can do is stop refining requirements and start clarifying risk.

Looking for more practical tips to develop your product management skills?

Product Manager Resources from Product Management IRL

Product Management FAQ Answers to frequently asked product management questions

Premium Product Manager Resources (paid only) 4 learning paths, 6 product management templates and 7 quick starts. New items monthly!

TLDR Product listed Product Management IRL articles recently! This biweekly email provides a consolidated list of recent product management articles.

Connect with Amy on LinkedIn, Threads, Instagram, and Bluesky for product management insights daily.

Spot on about surfacing risks instead of forcing consensus. I've watched PMs spin wheels on alignment workshops when execs hadnt decided which failure mode they could tolerate. The risk gradient framework is cleaner than most models. Default path vs judgment often gets politcal because stakeholders want it to favor thier domain. Framing as 'where does risk live' depersonalizes it nicely.